"Innovations for Formula One cars always make their way to cars for the public, and treatments for elite athletes are the same. After a while, they're available to everyone,” according Dr. Gino Kerkhoffs, Professor and Chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine at Amsterdam UMC and co-director of the Amsterdam Collaboration on Health & Safety in Sports (ACHSS).

Earlier this week, Amsterdam UMC began its third Olympic cycle as one of International Olympic Committee's (IOC) 11 Research Centres for the Prevention of Illness and Injury. And as Kerkhoffs alludes to, this time with a renewed focus on developing treatments for the general public.

Every four years, the IOC selects partners across the globe in order to stimulate collaboration, develop research programmes and amplify research results. Until the end of 2026, Amsterdam UMC, as one of three in Europe, may once again hang the five Olympic rings on the wall of their Sports Medicine facility. For Evert Verhagen, Professor of Epidemiology of Sports, Physical Activity and Health and Kerkhoffs’ co-director at the ACHSS, "The rings are sign of recognition of the work that we do clinically, in education and our research achievements.” But like Kerkhoffs, Verhagen sees this as a starting point and believes that it is "society who can benefit most.”

Unique status

Amsterdam UMC's status as a university hospital, a place where education, research and treatment are combined, is unique among the IOC Research Centres: "It's not uncommon to see an elite athlete doing rehab after surgery next to a cancer patient or a patient getting back on their feet after a traumatic injury," says Kerkhoffs. In his experience, this has benefits for both the patient and the IOC: patients "get an extra dose of motivation” and for the IOC it means that findings from injury prevention research can be directly applied to those with a history of injuries.

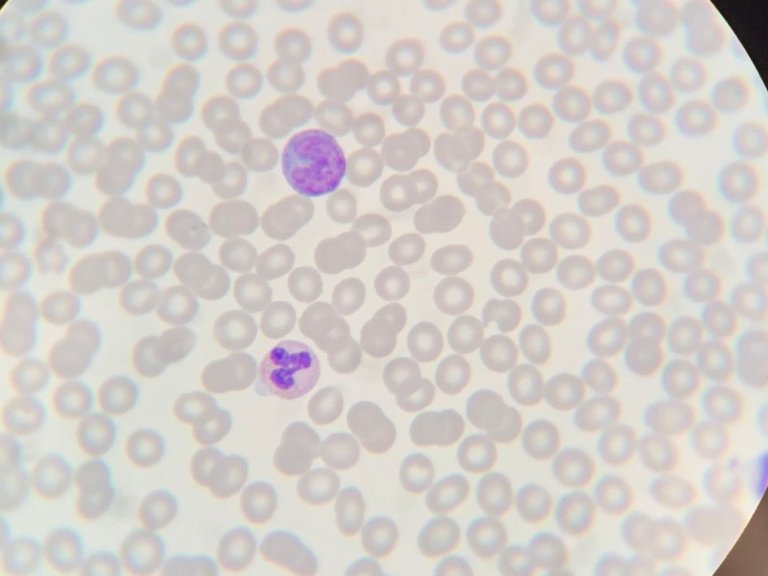

Injury prevention is the focus of much of the work done by Verhagen and this applies to both the casual runner as well as the 100m sprinter at the Olympic Games: "The body of an elite athlete allows us to research how far the body can go, and this gives us the chance to develop guidelines that fit everyone.” This research is also carried out together with other IOC research centres, for example by developing guidelines for how you should return to sport after an ankle sprain, the most common sports injury for both professionals and amateurs. Or investigating how to perform better cardiovascular screening. A development that would have consequences for both elite athletes and the general public.

The importance of recognition

The centre's ability to improve processes like those outlined above is only aided by the IOC recognition, and for Verhagen while the rings are naturally "beautiful to hang on the wall,” it's the recognition that's most important. As it allows the centre to tackle "questions of transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary science,” simply by letting other institutions see the work that is done in Amsterdam and opening eyes to the possibility of collaboration.

This also has a benefit for recruitment, the ACHSS has grown from 33 to 105 researchers since the first IOC recognition in 2016. In Kerkhoffs's eyes this has turned the ACHSS into its own version of the Olympics: "Everyone wants to take part but you can only fit so many people in.” An increase in personnel, also, inevitably, leads to more research.

Societal impact

For both Kerkhoffs and Verhagen, it's research that looks toward wider society that can have the biggest impact. In the Netherlands, half of the population are overweight, with more than half of Dutch adults not moving enough. While, in both cases, the Dutch perform better than the EU averages of 53% and 70%, getting people moving and keeping them moving is crucial for public health. Not just in terms of healthcare costs but by also contributing to an increased quality of life and to the prevention of many common physical and mental illnesses.

Keeping people moving, through injury prevention and improved rehabilitation, is something that Verhagen and Kerkhoffs hope to play a large role in as the Olympics get ready for Paris in 2024 and the Winter Olympics in Milan in 2026. Kerkhoffs: "I think it's important to really create the opportunity to have a positive impact on society. That's something for the next three years, it took us a while to get here but now we have more assets, more opportunities so we can have an impact on society while also working on our Formula One cars."