"The current system, with its unequal distribution of surveillance infrastructure, is detrimental to public health globally,” says de Jong. Currently, leading countries, mainly in Europe and North America sample "more than 100,000 times more than the countries, usually in Africa, at the bottom of ranking,” he adds.

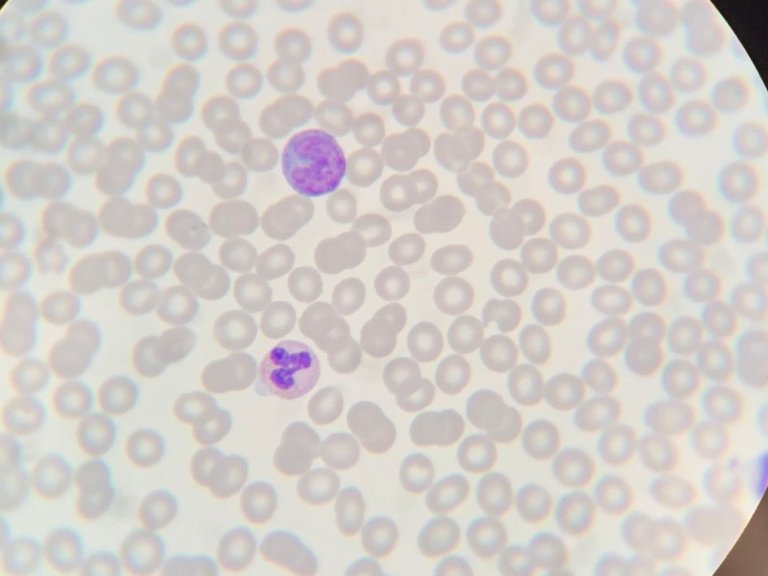

Genomic surveillance, the process of constantly sampling pathogens and analysing their genetic similarities and differences, has multiple benefits including the early detection of variants, as well as monitoring the spread of viruses. Understanding the spread can allow policy makers to make decisions on measures such as travel restrictions and quarantine protocols.

COVID as case

The benefits of genomic surveillance were evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where vaccines were quickly redeveloped based on the prevalence of a specific variants. However, this can only happen once a variant has been detected. A process which can take months in the countries that sample the least.

"With our current infrastructure, in countries with the lowest sampling rates, of around 0.01 per million inhabitants per week, a variant can spread to tens of neighbouring countries before it is detected,” says de Jong. This means that, in concrete terms, a variant that originated in Africa would take up to 160 days to be identified, where as a variant that originated in Europe would be spotted after just 30 days. "Indeed, 70% of the variants originating in Africa were spotted in Europe for the first time," adds de Jong.

More efficiency, not more money

In de Jong's view, the solution to this inequality is not to simply increase sampling infrastructure. But rather, that "relatively small increases in global sequencing output, in the right places, can profoundly improve global respiratory virus genomic surveillance in ways that even large increases in places with established surveillance infrastructure cannot", he says.

De Jong's research shows that variant identification can be reduced from "months to weeks”, if we were to reduce the global sampling capacity by 50% and redistribute the remaining 50% evenly across the planet. Something he believes should be a "global health priority".

From your genes to your jeans

Genomes are not the only target of surveillance that can benefit global public health. People, through the increasing prevalence of personal health devices such as smartwatches or tracking apps, like those deployed in the COVID-19 pandemic are a rich source of data for public health officials.

However, Sharifah Sekalala, Professor of Global Law at the University of Warwick, who also spoke at the symposium, warns that despite "better data leading to better products, services and healthcare," the benefits are being overshadowed by the practices of the companies who provide the services.

In Sekalala's view, much of the data is gathered unnecessarily by companies that ''hoard data to use as an asset.” She believes that politicians should do more to regulate those who are "extracting public data without public benefit.” A practice which is currently unchecked and leading individuals to "lose faith" in developments that could help combat real global health challenges.

Indeed, Sekalala believes that the current practices reinforce many of the inequalities that have been a feature of the public health malpractices in the past. Such as the exploitation of resources or the withholding of a voice from local communities.

Sekalala mentions the former practice of the British National Health Service sharing data with the British Ministry of Home Affairs in order to track down immigrants who were believed to be breaking immigration rules. "We shouldn't become complicit in collecting mountains of data that can be used to harm marginalised groups," concludes Sekalala. Instead, national organisations who wish to use health data should have conservations first, before they act. "We never what communities need, until we ask them ourselves," Sekalala concludes.