COVID-19 has had a devastating impact on vulnerable communities, particularly people from ethnic minorities and migrant backgrounds. Research from Amsterdam UMC already found that these populations have been severely impacted by the virus and were several times more likely to be infected with and die from COVID-19 compared to majority populations in high-income countries. Various factors, including poor social and economic circumstances, communication barriers, and health literacy contribute to this disparity.

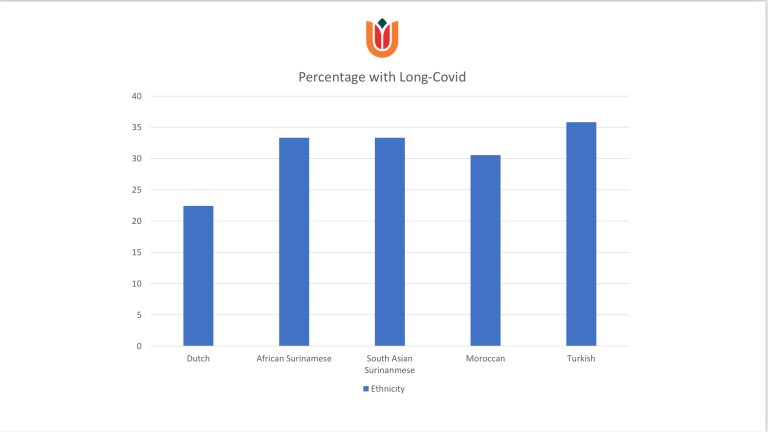

To investigate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on patients from diverse backgrounds, including Dutch origin patients, African Surinamese, South Asian Surinamese, Moroccan, and Turkish origin patients, Amsterdam UMC collaborated with the University of Copenhagen and Stockholm University to conduct a study.

Their findings revealed that about 26% of the patients who were hospitalized with COVID developed long-COVID. All the migrant groups had a higher risk of developing long-COVID than Dutch patients. Among the Turkish population, this risk is 50% higher than in the native Dutch population. Females, as well as patients who stayed longer in the hospital, were admitted to the intensive care unit, and received oxygen, were also more likely to develop long-COVID than those who did not.

The study also found that the experience of long-COVID symptoms differed between the groups. For example, experience of dizziness, and muscle and joint pain were highest among Turkish origin patients compared to other patient groups. On the other hand, experience of a racing heart, and trouble sleeping were highest among patients from Moroccan origin. Finally, the study found that about 14% of long-COVID symptoms were still persistent at one-year post-discharge, particularly among South Asian Surinamese origin patients.

According to the senior author of the paper, Professor Charles Agyemang, Professor of Global Migration, Ethnicity & Health at the Amsterdam UMC, the findings were not surprising as "the social determinants of health that shaped the disproportionately high rate of COVID-19 infection and deaths in ethnic minority and migrants are still at play."

"Many vulnerable populations in the community are suffering from long-COVID in silence due to a lack of awareness of the condition in these communities. Promoting awareness about long-COVID and facilitating easy access to healthcare and services in ethnic minorities and migrant communities and other vulnerable populations is crucial to addressing these health inequalities," adds Agyemang

The lead author, Dr Felix Chilunga, an Assistant Professor at the Amsterdam University Medical Centre, added that "patients with long-COVID are likely to face functional limitations in their daily lives, such as being unable to work or do activities of daily living. The extent of these limitations is still unknown. Therefore, checking the extent to which long-COVID affects daily activities can ensure a targeted approach to the symptoms that contribute to the greatest limitations."