This month the Dutch TRIDENT studies aiming at responsible implementation of the Non-Invasive Prenatal Test (NIPT) in the Netherlands will end. As a result of the positive outcomes of these studies, NIPT becomes a structural part of the Dutch national prenatal screening program and will from now on be freely available for all pregnant women in the Netherlands.

NIPT is a maternal blood test to investigate whether an unborn child might potentially have Down, Edwards or Patau syndrome. Researchers from Amsterdam UMC have been involved in the development and implementation of this test from the start, working together in the multidisciplinary Dutch NIPT Consortium. Erik Sistermans, Professor of Human Genetics at Amsterdam UMC, believes "that such an approach might prove very effective to implement NIPT in more countries across Europe”.

For many years, NIPT in the Netherlands was available as part of two scientific studies performed by the NIPT Consortium: TRIDENT-1 and TRIDENT-2 (TRIal by Dutch Laboratories for Evaluation of Non-invasive Testing). Aim of these studies was to investigate all aspects for responsible implementation of NIPT in the Dutch prenatal screening program. The TRIDENT studies not only led to successful implementation of NIPT, but also to a range of scientific publications. In February 2023, the NIPT Consortium received a prestigious price, the ZonMw Pearl, for research with high societal impact.

Across Europe, only the Dutch and Belgian health services offer NIPT to all women as a first-tier test part of their national screening program. In many other countries the availability varies, sometimes NIPT is only offered as a second-tier test after the combined test, sometimes NIPT is offered commercially, but not as part of a national screening program. “This splintered picture means that there is no consistent offer throughout Europe when it comes to an important issue such as prenatal testing,” says Sistermans.

Development

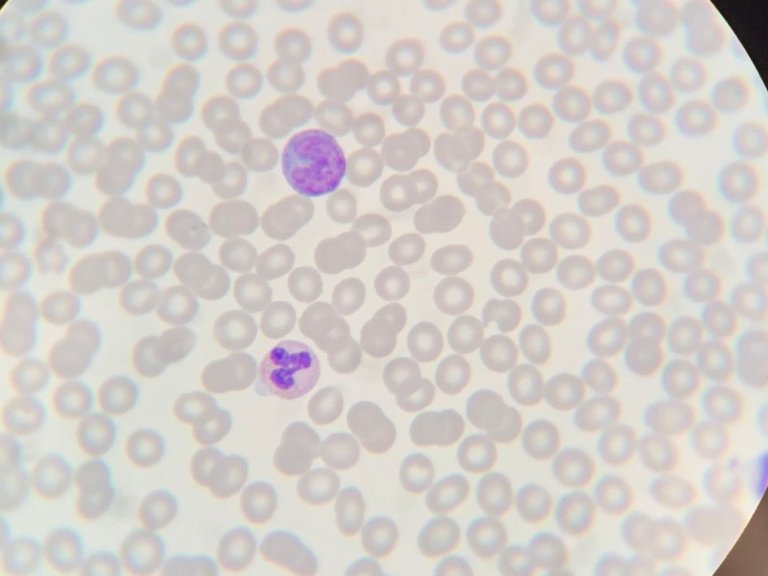

The discovery that cells from the placenta were present in the mother’s blood dates back to the end of the nineteenth century. By the 1940s, it had become clear that, in addition to these cells, the mother’s blood contains cell-free genetic material from the unborn child. Only at the end of last century Dennis Lo, professor of Chemical Pathology from Hong Kong, found a way to interpret the traces left by the unborn child in its mother’s blood. Sistermans explains that “What you see in the blood are actually tiny pieces of DNA. A great deal of analytical processing and a powerful computer are required to analyse these pieces of the puzzle and obtain meaningful information from them. However, at that time, genetic technologies were not sufficiently advanced to exploit this information.”

By 2008 that had all changed. Two independent groups led by professors Dennis Lo and Steve Quake described how to use those puzzle pieces to find out whether an unborn child might potentially have three copies (trisomy) of chromosome 21, which causes Down syndrome, or of chromosomes 13 or 18, which give rise to Patau or Edwards syndromes, respectively.” Assisted by Professor Cees Oudejans from the Department of Clinical Chemistry at Amsterdam UMC, then VUmc, Dennis Lo published another paper describing a large-scale validation of the use of cfDNA for prenatal testing.

Advantages

Since 2014, the NIPT has been offered in the Netherlands to pregnant women who are at increased risk of having a child with Down syndrome based on first trimester combined testing or their medical history (TRIDENT-1 study). In the combined test, the risk that the unborn child might have a condition of this kind is assessed using the thickness of the nuchal fold, a layer of fluid under the skin at the back of the neck, which is measured using an ultrasound scan, in combination with a blood test and the age of the mother.

Those mothers who got a ‘positive’ result in the combined test then had to undergo invasive testing to determine whether their unborn child actually does have Down’s syndrome. However, the latter tests involve an approximately 2 in 1,000 risks of miscarriage.

“The evaluation of TRIDENT-1 showed that offering NIPT as contingent test to women with increased risk based on the combined test or medical history greatly reduces the number of invasive tests, as the majority of women will receive a low-risk NIPT result, and follow-up testing is not recommended,” says Sistermans.

It soon became clear that the NIPT had major advantages over the combined test. This led to the TRIDENT-2 study, in which NIPT was offered as alternative for the combined test as a first-tier screening test at comparable costs. Follow-up invasive testing is still needed for confirmation after a high-risk NIPT result, but the chance of having a false alarm is much lower than with combined testing.

Informed choice

These days, the combined tests are not carried out anymore in the Netherlands, as most women who wanted prenatal screening, preferred NIPT. However, many women still don't opt in for screening. Dr. Karuna van der Meij, showed in her PhD thesis at Vrije Universiteit and Amsterdam UMC, that most women make an informed choice for screening with NIPT, and that the many advantages of NIPT did not lead to routinization, or uncritical use of screening.

Lidewij Henneman, Professor of Patient Perspectives at Amsterdam UMC, still has a few key questions. “What will happen to the uptake of screening if the test become free? Do women still make an informed decision? Moreover, one of the things many people wonder about is why ‘only’ 55% of pregnant women in the Netherlands take part in screening, which is much less than neighbouring countries. A Dutch study showed that women from deprived areas are less than half as likely to opt for an NIPT than women who live elsewhere, which may be partly explained by the costs for screening.

An alternative explanation for the relatively low national screening uptake might be that we, in the Netherlands, tend to take a more positive view of people with Down syndrome, as compared to for example Belgium, as shown in a recent study. It might also be due to the carefully considered way in which screening is offered here, and to the associated counselling process.”

Future possibilities

With his research group, Erik Sistermans is exploring a range of options that go beyond the current NIPT. “In collaboration with others, although the TRIDENT studies are completed, the Dutch NIPT consortium will continue as a research consortium. One example of the ongoing collaborations, together with our counterparts at Radboud UMC in Nijmegen, we are already exploring the options for using the NIPT to detect traces of cytomegalovirus. In children, this can lead to congenital deafness and various other abnormalities.

Furthermore, adding the examination of specific fragments of RNA to the NIPT may help us to identify another risk to mother and child – pregnancy-induced hypertension and toxemia, also known as preeclampsia. In a 2020 trial among 161 pregnant women, it was found that the NRIP1/ZEB2 ratio was upregulated in pregnancies with pre-eclampsia or trisomy 21. We now want to validate this technique on a larger scale.”’

Sistermans and Henneman expect the range of conditions that can be detected using the NIPT to gradually expand. “As before, we will aim at using the NIPT consortium’s multidisciplinary approach to explore the possibilities around providing this service, in a carefully considered way, to expectant parents.”