Agyemang believes that while this is frustrating for doctors who are left with paracetamol as their only safe prescription, poor communication has larger, knock-on effects for not only the patient but also their friends and family: "As soon as people leave, they go back to their community and say 'I spent all my time going there, I had to take a bus and all I got was paracetamol' and this word spreads.”

But for Agyemang, this is just a small part of reason that migrants have little trust in their new home countries. The media also don't help: "the media tend to, unfortunately, issue negative stories about migrants. This undermines social cohesion of migrants as they lose trust in the media because of how they are portrayed."

Media portrayals are not the only factor that reduce a migrant's trust in their new country. Agyemang notes that when migrants first arrive in a country, they often face many challenges including legal issues and are left with "unpleasant" memories of state bureaucracy. Memories that are hard to erase due to the language barrier.

A lack of trust in the system and poor language skills to navigate it can have massive effects on the health of individuals. As Agyemang puts it, "migrants just do not have the same access as the general population and this has consequences. In the last available Dutch figures, those from low-and middle-income countries generated up to 20% more healthcare costs per person than the general population. Migrants are also between two and four times more likely to be depressed, have lower life expectancies and also rate themselves as less healthy than the general population.

Despite these catch-all statistics, things are not so simple as "migrants are less healthy". In Agyemang's experience "some people think that migrants are monolithic" and this limits both our societal and healthcare understandings.

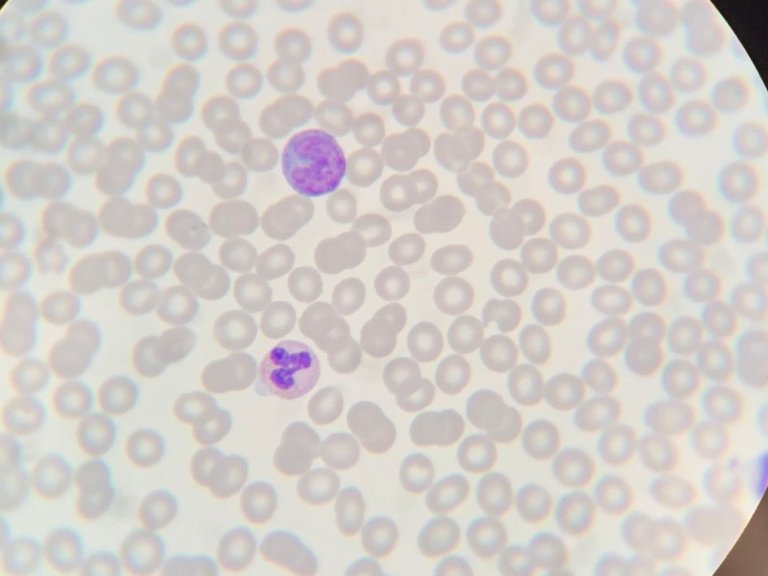

For the past twelve years, Agyemang has been one of the lead researchers in the HELIUS Study, tracking the health of 25,000 Amsterdammers, with the aim of discovering the health disparities between population groups and their causes. For Agyemang, “the key to a healthy population is understanding the population”. These differences are stark: Moroccans are more likely to have diabetes, those with a Turkish background are more likely to have Asthma and, both, African Surinamese and Ghanaians are more likely to have high blood pressure.

These issues are created by a combination of cultural factors, from a difference in diet to one culture being "more stressful” than another but, despite the varying causes, Agyemang believes the solution is the same: creating awareness and providing people the necessary means in order to enable them to make healthier choices. Trust is key in being able to create this awareness: "We need to tell people about health in a way that they understand, through the people that they trust, in a place that they feel comfortable".

Building trust is then essential and, as Agyemang hints, this can be helped by having a more representative health system: "We need to build things in such a way that the health system reflects the population itself – in order to give people, the feeling that they can trust it.”

Studies have shown the perceptions of fairness can build trust but Agyemang believes that the current state of affairs needs more fairness and equal opportunities: "People come in and the only people they see like themselves are those in the lower end of the career ladder, for example, cleaner. Then, people lose trust."

A new health system is just the start, however. For Agyemang investment in migrant communities, before they reach the hospital doors, is desperately necessary: "If you neglect the health of these people, more and more people will come to hospital, and this will cost you a tremendous amount of money. Why spend thousands to treat someone for stroke, if you could have helped them to improve their blood pressure on the ground. So, the issue here is a win-win. If you don't do it, the society pays a very, very heavy price.”

However, at the last pre-COVID estimates, EU governments, only spent, on average, 2.8% of their health care budgets on preventative measures, such as regular check-ups. And most of this spending doesn't reach those outside of the general population. Leading to some of the aforementioned health problems.

Agyemang believes that the reaction of governments across Europe to COVID has shown how much is possible, as well as how much could have been saved through prevention strategies: "When COVID-19 hit and a lot of people ended up in intensive care – a large number of them were migrants or those from a low socio-economic background because these people had issues with chronic conditions and they tended to be frontline workers. All of a sudden, the governments had money to treat people in the intensive care and they spent billions. If they had actually used a fraction of this money to keep people healthy, they could have saved a lot.”

The combination of an effort to increase trust between all groups in society and more, targeted, preventative health care, might cost money in the short-term but by giving everyone "an equal opportunity to be healthy," Agyemang is certain that "we can help people make a change in their lives.” A change that would go a long way to reducing not only health inequalities, but also societal inequality.

This is the second of three interviews looking at the relationship between health and our society. Next week, we speak with Associate Professor Roeline Pasman about acceptance and the end of life.