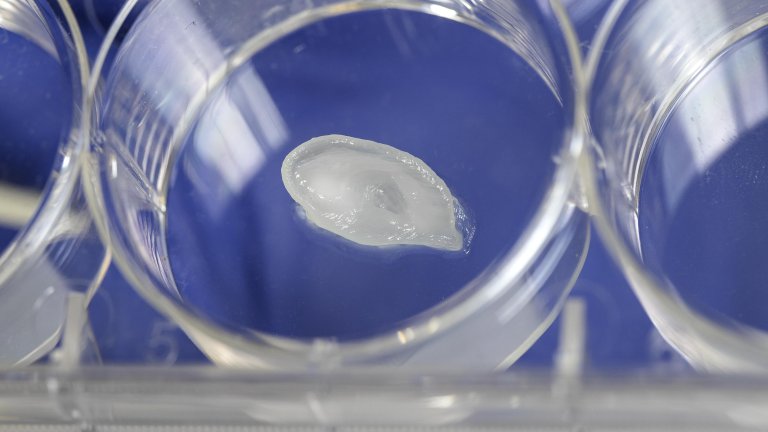

So too in the laboratory of Arthur Bergen, Professor of Molecular Genetics, where the ear was one of the first objects that molecular biology post-doc Eszter Emri produced during a recent demonstration of their new 3D printer. As the print head shuttled delicately back and forth, the unmistakable form of a small, shiny white ear took shape in the petri dish.

But the finesse of this demonstration does not lie in the complexity of the shape, Emri asserts. “We have printed this ear using ordinary Nivea Cream,” she says, not without a touch of pride. “The art lies not so much in the shape as in the softness of the material we use. How do you prevent fluid material from simply running out of the printer? How can you control the water content needed to ensure the fluidity of some materials so that it evaporates at just the right moment? Those are the problems that occupy us in our experiments with 3D printing.”

Text: Rob Buiter

Photos: Marieke de Lorijn

The full version of this article (in Dutch) was published in our popular-science magazine Janus.